Navel-gazing: depictions of interiority in video games

Video games need to have concrete, readable, and operable representations of the entities in the game. Some video games depict buildings or opponents. Sometimes video games depict thoughts, feelings, or aspects of a person's personality: that's what we're going to talk about. This is a comparative review of different depictions of the inside of a person's mind, what in different video games. Specifically, we're going to look at The Sims, Rimworld, Cultist Simulator, Michael Brough's A Sense of Connectedness and Nikhil Murthy's The Quiet Sleep. Psychonauts and To The Moon are great games, and they do depict interiority, but I'm not going to discuss them.

The Sims

The Sims is a virtual dollhouse game, where the player designs and furnishes a house and controls semi-autonomous simulated humans called "sims" who live there. Since The Sims is the oldest of these games, I'm going to use its depiction of interiority as a model for the others.

There are need bars, such as sleep-need and toilet-need, and they combine to form an aggregate mood bar. This mood bar has a threshold which is pretty high, but not exactly at the top. Some activities are only possible for a sim when their mood is above this threshold. These activities are, broadly speaking, ones that many people have aversions to or have to be in the mood for.

Aside: Andrew Critch has a list of aversive activities at the beginning of his talk on Aversion Factoring: "Homework, grading homework, singing, dancing, public speaking, asking someone on a date, math, taxes, exercise, programming, debugging programs, filling out forms, dealing with bureaucracy, talking to strangers, re-approaching friends you haven't talked to in a while, applying for a job, applying for college, applying for funding, accepting compliments, giving compliments." This is not a list taken from the Sims, it is a list of real life aversions, but it's perhaps representative of the kind of activities that low mood might block within the Sims.

Sims have relationships, which are represented by a number regarding how close one sim is to another sim. When relationships get high enough, they can be either romantic relationships or not.

There are skills such as Cooking, Cleaning, Painting and Logic, which have a number regarding how expert the sim is at the skill.

Sims can have a career, which consists of a sequence of jobs from entry-level to maximum prestige / seniority / pay, which separated by promotions. Going to your job with good skills and good mood gives better progress towards the next promotion. Furthermore, each promotion has some requirements, such as "these skills must be at or above these numbers", and "you must have at least this many friends". For example, "Organ Donor" is an entry level job in the Medical career.

In later Sims games, there are desires (variously called wants, wishes, or whims), and moodlets. Desires are something like small optional quests, for example, to buy a boat, or attend a cooking class. I won't describe them in detail here. Moodlets are something like temporary influences, positive or negative, on the Sim's mood, that have a little bit of text describing how the moodlet was obtained. The Moodlet system leads to an initially-unknown, explorable and gradually-discoverable system of mood management (more about that later).

These mechanics and depictions in The Sims are not arbitrary, they're very directly motivated by the overall gameplay. There are a lot of goals or fantasies that a player might arrive to The Sims with - you might want your sim to have a particular house, particular clothes, particular furniture, to have a prestigious job, to be skilled at one thing or another, to have a particular kind of relationship or a family. Some of these goals (house, clothes, furniture) correspond within the game to having money, which can be obtained via a job. Other goals (job, skill, relationship) connect to these numeric ladders in the user interface. Actions that move the sim up these numeric ladders generally correspond to aversive actions.

So at first glance, the gameplay loop of the Sims consists of addressing your Sims' basic needs, in-order-that they have mood high enough, in-order-that they can make progress on their skills and relationships, in-order-that they make progress in their career ladder, in-order-that they have money, in-order-that they can buy more house and more furniture that addresses their basic needs more completely, in-order-that they can do more self-actualization and fulfill player goals or fantasies. (The text in the game, at least in the original Sims, pretty clearly pokes fun at this materialist/capitalist take on Maslow's hierarchy. Later Sims franchise entries dilute and undercut the pointedness of the joke by unironically including a real-money storefront.)

Of course, the real gameplay loop of the Sims consists of starting to play with the apparent gameplay loop, and then getting distracted by something: either the narrative that you project into the world, or the aesthetics of the world, or the simulation as a system to be explored, or something, until you are playing with the Sims as if it were a toy like a ball or a sandpit, which is characteristic of Will Wright's game designs, as I understand them.

Rimworld

Rimworld describes itself as "A sci-fi colony sim driven by an intelligent AI storyteller." and "RimWorld follows three survivors from a crashed space liner as they build a colony on a frontier world at the rim of known space. Inspired by the space western vibe of Firefly, the deep simulation of Dwarf Fortress, and the epic scale of Dune and Warhammer 40,000."

In a lot of ways, Rimworld's depiction of interiority is just a remix of the Sims, but I think seeing just how similar these systems can be highlights the differences that remain, and the very substantial differences that are coming up in the other games. Aside: In The Sims, the human-like entities are called sims; in Rimworld, the human-like entities are called pawns.

The list of need bars is variable and interacts with Rimworld's system of personality traits. Some pawns are alcoholic and have an alcohol need bar and others do not. Many pawns have an outdoors need bar, but some pawns are undergrounders and do not.

Opinions in Rimworld are similar to the Sims Relationships - a single number representing "what X thinks of Y", and a more crisply discrete category such as "Lover".

Skills in Rimworld are very similar to the Sims; bars and numbers that represent how skilled a pawn is at an activity. Skills in Rimworld are generally advanced by doing the activity in question for its primary effect.

Rimworld does not have a careers system in the vanilla game, though the titles and psycasts systems in the Royalty add-on does function as a careers system. Both the Sims career system and Rimworld's titles system are techniques for the game designer to gate something that is relatively cheap for the game designer to manufacture and give away - "the next promotion" - that nevertheless the player wants (or at least a default goal that the player will pursue, in absence of another idea of how to play), and instruct the player to accomplish various arbitrary tasks, quests, under various arbitrary constraints, like "while working from 9-5" or "while maintaining a luxurious bedroom". Puzzle games like Sokoban call this same kind of thing "levels".

Moodlet-like thoughts are heavily used in Rimworld.

Rimworld aggregates individual thoughts to form an overall pawn-wide mood, but it doesn't gate aversive actions behind high mood like The Sims does. Rimworld instead has a system of inspirations and mental breaks (I have not played it, but I believe this inspirations-and-breaks system was based on Dwarf Fortress). A pawn with high mood may become inspired, and gain a temporary bonus to, for example, craft very high quality items or furniture - this doesn't affect gameplay much. A pawn with low mood may experience a mental break, going out of control of the human player entirely and engaging in a characteristic pattern of bad behavior, such as lighting things on fire (if the pawn is pyromaniac), or starting a fight, or insulting someone, or going on a sad wander.

In Rimworld, the player is subjected to periodic events, such as invasions, but also disease and periods of particularly bad weather. There are different "storytellers", which function something like difficulty settings controlling these periodic events, but even on the non-escalating storyteller setting there is a phenomenon (that pawns' expectations are affected by overall colony wealth) which leads to a gradually escalating complexity as your colony's infrastructure grows.

Eventually, your Rimworld colony may fail. The way the failure occurs is important though: it's likely a domino cascade through the moodlets and break system. For example, a storyteller triggered event that was handled imperfectly (due to the escalating complexity) might kill a beloved pet (A), which then pushes a particular pawn into a pyromaniac break (B), which then damages some other pawn's bedroom, which eventually triggers their break (C). This domino cascade is real in that A really causes B which really causes C, but there's also little snippets of text attached to these events (mostly via thoughts) that invite the player to read this sequence as a narrative.

This emergent narrative arc "struggle to rise, against adversity, tentative hope, and then almost-inevitable cascading tragedy" is exactly what Rimworld promises, and its divergences (such as that total colony wealth setting mood expectations, and the mental breaks system) from the Sims model are directly towards achieving that arc.

Cultist Simulator

Cultist Simulator describes itself as "a game of apocalypse and yearning from Alexis Kennedy, creator of Fallen London and Sunless Sea".

Aside: I understand Alexis Kennedy was credibly accused by two women of predatory behavior. I don't endorse the Death of the Author; I do not believe that the work is best understood separate from the people who created it, and so I was conflicted about whether to write about Cultist Simulator at all. However, I do think there are many aspects of Cultist Simulator's design that are interesting and worth talking about.

Cultist Simulator is deliberately obscure, and its storytelling is elliptical, apophenic, procedural and emergent, and I don't want to entirely spoil it. However, I will attempt to describe it: You may find yourself experiencing tsundoku, buying books faster than you are reading them. A pivotal point in your story might be when your favorite bookstore runs out of occult books to sell you. Your book-lust might lead you into committing crimes. You may commit further crimes in order to cover up those earlier crimes. You will likely found a cult. You will likely recruit one of your acquaintances to your cult. You may have to watch as your follower is tried for your crimes, and the best way to save them might be to dream up a Favor from Authority.

There are three things in Cultist Simulator that are most analogous to Needs from The Sims - Funds, Hunters, and Ambition. In order to not starve, you must feed Funds to the Time process periodically. Each of these periods is referred to within the game as a "season". Each season also includes a draw from a deck of Seasons.

During the Season of Adversity, the Hunters act against you. In order for you to avoid the Suppression Bureau, you must first, avoid generating Notoriety, or (when inevitably you do generate Notoriety) second, prevent a Hunter from obtaining it and turning it into Evidence, or (when inevitably the Hunter does turn it into Evidence) third, dispose of the Evidence before the Hunter brings you to The Trial.

During the Season of Ambition, you must deal with your character's own ambition, creative or destructive urges and/or exotic cravings. For example, in the opening of the game, before you have decided upon a goal, when the Season of Ambitions comes around, you must deal with Restlessness - an Influence that is fairly easy to deal with once you know how, but the various ways to deal with it tend to either disrupt your routine or advance the story towards one ending or another.

Similar to the Sims, relationships are a major part of Cultist Simulator. Some people start as acquaintances, become followers and rise in rank within your cult. Some people are enemies, and are likely to stay enemies. Some people are patrons and are likely to stay patrons. There's a romance system, but it's fairly unobtrusive, and I won't go into it.

There are three attributes: Health, Passion, and Reason. These attributes are somewhat similar to skills from The Sims in that there are fairly straightforward ladders to improve them. But Cultist Simulator also deals with pursuing and collecting lots of different kinds of knowledge: lore, rites, and rituals. Owning books is a kind of pre-knowledge. Locations in Cultist Simulator are kind of a pre-book, because you can send an expedition to a location, and (if your expedition is successful), obtain treasures, which generally include books.

In order to not starve, you must feed Funds to the Time process periodically; there are many different ways to obtain Funds, and one of them (clerking) is similar to Sims in that it is exhausting and frustrating, and there is a promotion ladder.

There are influences, which are a bit like Sims moodlets or Rimworld thoughts, in that they are short term transients, but they do not aggregate to an overall mood. Influences are generally ambiguous, having both advantages and drawbacks. Fascination is an example: If you have a Fascination on the board when Season of Visions comes around, then the Season of Visions will be promoted to the Seeing Things process, which is a kind of illness. The Seeing Things process is bad because it can last a long time, and if Seeing Things absorbs 3 Fascination, your story ends (the insanity ending). On the other hand, Fascination can be used in some recipes.

Many Influences have a particular structure to their advantages and drawbacks. They say to the player something like "Either use me well in the next 90 seconds or I will decay into a less-pleasant-to-deal-with Influence". For example, A Consciousness of Radiance decays into Fascination.

The gameplay loop of Cultist Simulator consists of, initially, trying to learn how to manage your needs and influences (not starve, stay healthy, sane, avoid despair), while some periodic "needs" (suspicion, ambition) are more like Rimworld's storyteller-invoked incidents.

Often, figuring out how to manage your influences is actually, literally, the same insight as figuring out how to Work with your influences, or how to use your influences in your Art, so trying to figure out how the game works and how to keep your head above water naturally leads to curiosity about the system of magic depicted within the game. Of course, any time you try something new, some hypothesis about how the game works, it might turn out badly, producing a cascading effect that damages your routine, and therefore your health or your sanity.

Cultist Simulator is about seeking occult secrets, trying to figure out magic, and the danger of this pursuit.

Michael Brough's The Sense Of Connectedness

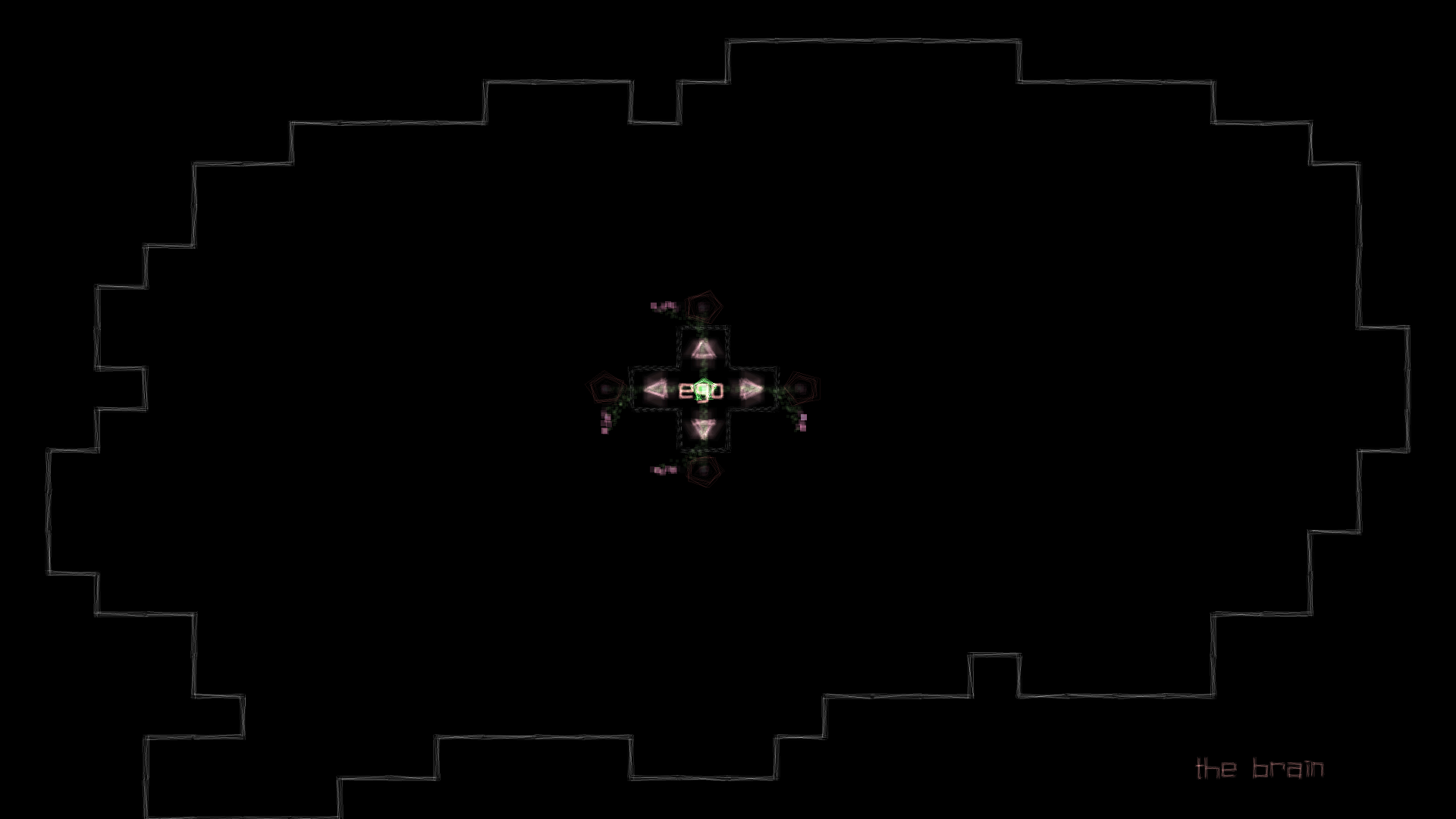

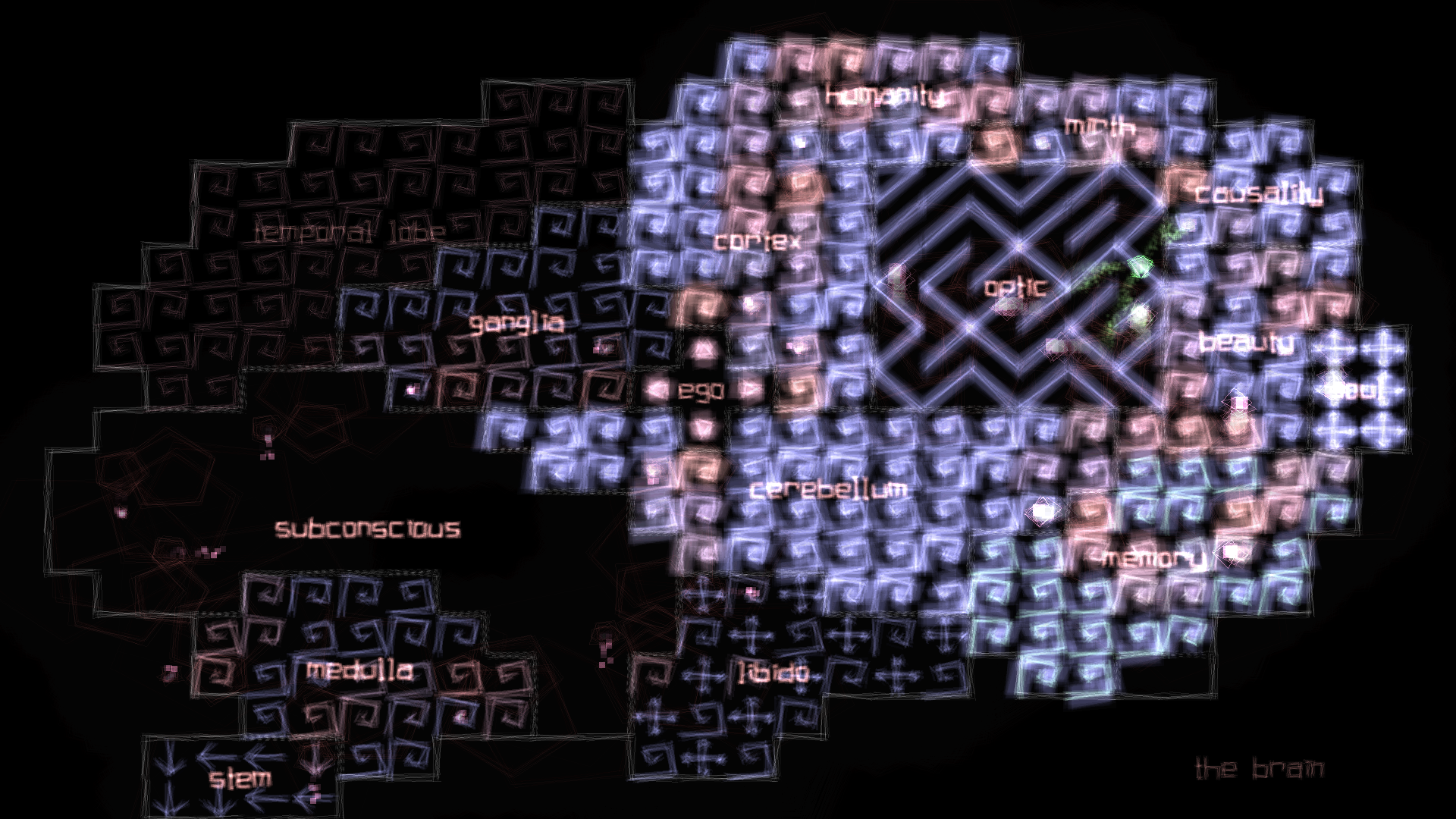

Michael Brough's The Sense of Connectedness is a mysterious and trippy game that depicts a brain. There is a spot labeled "ego" that periodically emits little lights that move through various suggestively-named regions, such as "ganglia", "cerebellum", "subconscious" and so on, and (at least initially) eventually fizzling out. You control a green light that can move around and can "flip" neurons, redirecting the flow of little lights, a bit like Pipe Mania crossed with a Cellular Automaton, specifically Langton's Ant. The beginning of the game consists of exploring the regions gradually outward from "ego", and gradually learning the rules, which are slightly different in the different regions.

Eventually you realize that you "die" - which is simply a red glow and a teleport back to Ego - if you go too far away from the flow of white lights, and so the way to explore is by rearranging things so that the you gradually light up different areas. Eventually, you can light up so much of the brain that the glow effect makes it hard to perceive what is going on.

There is little in The Sense of Connectedness that relates to the Sims-based framework that I've been using so far - no needs, no relationships, no skills, no job. There are a lot of short term transients, sure, but they are not recognizably moodlets, thoughts, or influences, more like "this part is lighting up, nice, but that part is about to go dark, hmm".

Like Cultist Simulator, but unlike The Sims and Rimworld, the game camera focuses only on the inner experience - the outer world is not depicted at all. Like Cultist Simulator, there is no tutorial, and the gradual exploration and learning of the mechanics is a big part of the gameplay.

The mysteriousness and exploration mechanic gives the player a sense of trying to figure something out. The brain theming, and the parallel between the player's gradual growth of knowledge of how the game works, and the way the the brain gradually lights up, very successfully gives a sense of being a person who is trying to figure themselves out.

Nikhil Murthy's The Quiet Sleep

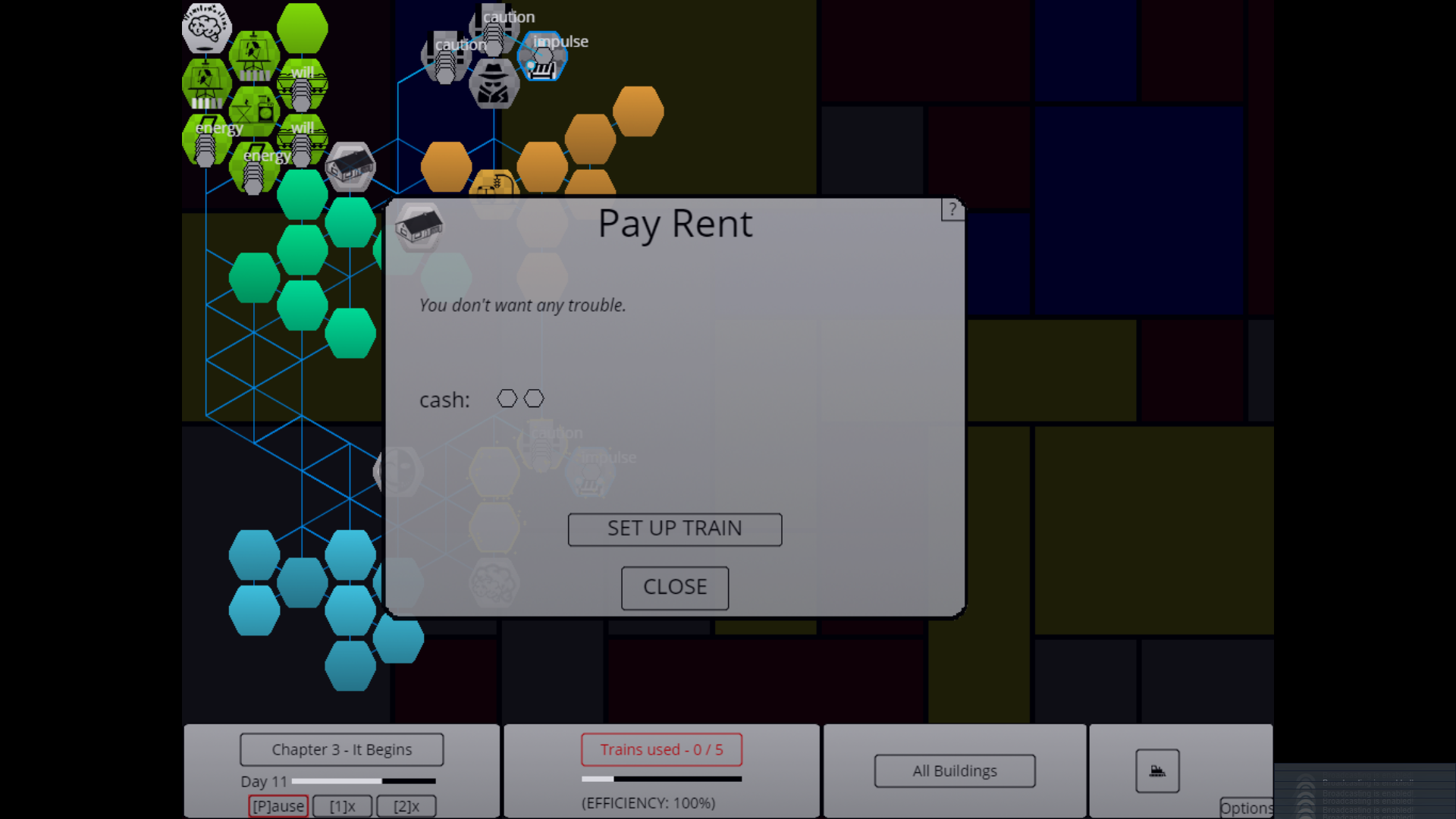

In its first devblog, Nikhil Murthy describes The Quiet Sleep: "My elevator pitch for this game is "Inside Out as a tower defense/city builder." Eventually, it is described as "a simulation/tower defense game set in your mind. Build out different parts of your personality to keep a handle on your emotions and to achieve your goals!".

Like Cultist Simulator and The Sense Of Connectedness, and unlike The Sims and Rimworld, the camera of the game points fixedly at the inner experience, and the outer world is not depicted. Like The Sense Of Connectedness, there is a central point, called Self, that emits little things which are called Trains (as in "train of thought"), and the map is divided into named regions. Where the first few regions in The Sense Of Connected are named after brain anatomy, the first few regions in The Quiet Sleep are named after personality traits or broad concerns: Adulthood, Homeland, Missing Home. Also unlike The Sense of Connectedness, there is no Pipe Mania mechanic; instead you schedule the trains to go to particular stops, and they pathfind their own way there without difficulty. The trains are created at the Self hex and then traverse various hexes before terminating somewhere, building or refilling a tower, defense, or goal.

One Tower within Adulthood is Will Mine, which produces a currency called Will which is used to build Towers and Defenses. Another tower is Energy Spring, which produces a currency called Energy, and a third tower is Do Chore, which converts Energy into a currency called Chores.

Defenses are Towers that do not produce or convert currencies. Rather, they protect the Self from Creeps - surges of emotion - by calming them. For concreteness, some early defenses are Painting and Walking.

Goals are like Towers, but you don't place them, they appear as you progress the story. They're something like a quest, in that you work to fulfill them, collecting "5 will" or "3 Murloc eyes", and then they go away (and presumably advance the story).

There is a mechanic, called "Pay Rent", which is similar to the Time process in Cultist Simulator. However, there is little else that can be connected to the idea of "needs" from the Sims.

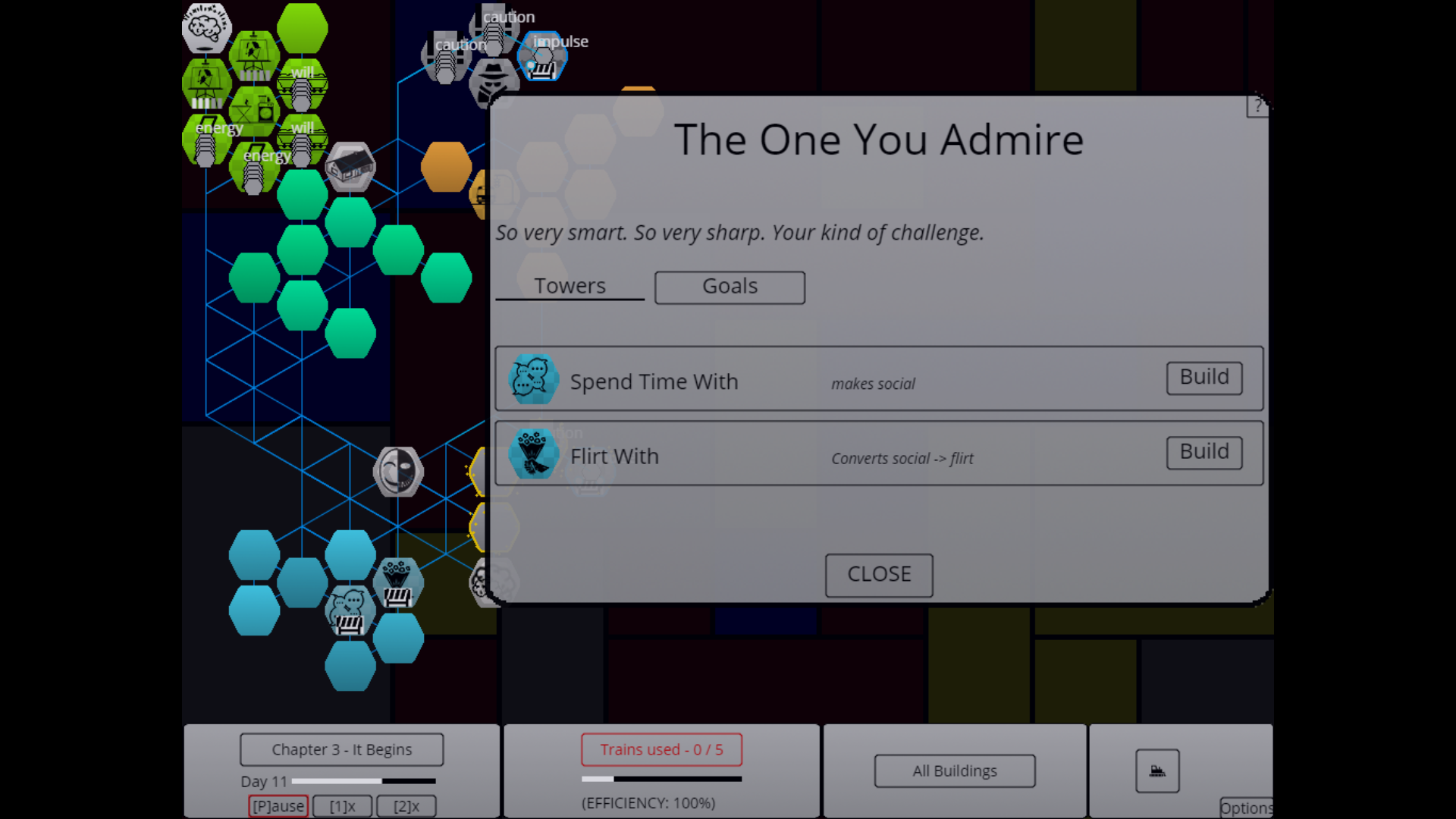

The Quiet Sleep depicts relationships as regions, just like personality traits. For example "The One You Admire" is the name of a region. By building towers in that region, you can build the relationship. The potential nuance of relationships in The Quiet Sleep is amazing. The Quiet Sleep can depict which internal currencies you are investing in the relationship, how eagerly or frequently you invest, what compromises or sacrifices you made elsewhere in your mind in order to obtain those currencies and what you are getting out of the relationship - or to say it in another-, perhaps less transactional- manner, what leaning on the relationship does to the system of your mind.

Similar to A Sense Of Connectedness, there's very little modeling of skills or knowledge.

In order to Pay Rent, you need the cash currency. The tower that produces the cash currency is probably a job, and figuring out a psychological defense against surges of anger created by casual racism during the course of doing the job is a fairly pivotal point of the first story.

There are regions, such as Threat, that seem to appear spontaneously and seem to spawn specific towers spontaneously, and those kind of towers often emit Creeps, which look a bit like Trains, but move inward towards the Self, where Trains generally move outward. Creeps can be defeated by Defenses. This dynamic, the creeps moving inward, is the tower defense part of the game.

I am sad to say that unlike the other games I mention, I do not find The Quiet Sleep fun. I think it is a narrative game design tour de force, and yet it is like pulling my fingernails to get myself to play it more.

What can we take away regarding navel-gazing in videogames?

Mystery, Extensibility, and Explorability via Antiobjects

You can make a game both extensible and explorable by attaching little fragments of behavior to lots of particular items. So for example, you can make the game "The Sims" bigger by adding new furniture, or new moodlets, and because the smarts of the Sim are actually aggregated from all the furniture or moodlets, the sims "magically" know how to use the new item or moodlet.

This design pattern is close to what Repenning called Antiobjects though 1) Repenning connects the idea to pathfinding. The pattern I am referring to has no necessary connection to pathfinding or regular grids of any kind. 2) Repenning suggests that this design pattern is in some sense not object orientation, but it's actually normal good object oriented design - it's also close to what Gamma et al. called the Strategy Pattern.

(I am not a linguist but) I think there's a quality of some linguistics theories, Head Phrase Structure Grammar among them, called "strong lexicalism", that grammatical competence is distributed and indexed by words. So that means that you can extend a language's grammar with a new word, which comes attached with some behavior, idiosyncratic rules about how it can be used. Head Phrase Structure Grammar's strong lexicalism is another example of the Antiobjects pattern.

Cultist Simulator is definitely written with this Antiobjects pattern. Someone might at first imagine that the game's internal architecture has a list of cards, with their names, descriptions, art and so on (and it does) and only separately a list of recipes like "you can combine A and B using C and after 60 seconds you form D and E". However, the recipes are actually card-indexed, so when a modder adds a new card, they also, in the same paragraph of XML, add the recipes that that card provides or provokes. Any apparent symmetry in recipes like "you can combine A and B in either order [...]" is actually an illusion or artifice. In fact, every recipe has a "head card" which has the behavior of the recipe attached.

If the internal architecture of the game is sufficiently readable by the player, the player's mental model of the game might grow over the course of playing the game, in a highly analogous manner to the game's behavior gradually growing richer as more items are added during development. This phenomenon might be called "Ontogeny (the time course of the development of the player's mental model while playing) sometimes recapitulates phylogeny (the time course of the game's development)". Most of these games have a significant exploration aspect to them, though Sims and Rimworld put their narrative-generator aspect in the foreground, and they background the exploratory aspect, something like "merely learning how to play", while Cultist Simulator, The Sense of Connectedness, and The Quiet Sleep, are fairly mysterious, and exploring and learning the game is a major part of the gameplay.

The Use of Apophenia

Speech bubbles in the Sims show glyphs, and it's easy and fun to "read into" the sequence of glyphs appearing in the speech bubbles, imagining a conversation that fits the characters and the sequence of glyphs.

Perhaps inspired by this phenomenon in the Sims, Failbetter Games described "fires in the desert" as a model for their variety of storytelling in their game, Fallen London, in a narrative engineering blog post. "Imagine a desert, seen from above. Paths lead between the villages in the desert. When travelers cross the desert, you can clearly see the route they take, where they stop off, and so on. But what if night has fallen? Then, all you can see are the little fires in the village. Occasionally, travelers emerge from the darkness and sit by the fires for a while, and then move on. But the routes they take between those fires belong to them alone."

Perhaps inspired by Failbetter Games blog post, Tynan Sylvester wrote "The Simulation Dream" a blog post advocating apophenic storytelling and referencing The Sims and Dwarf Fortress.

I think of apophenia as related to the Eliza effect. The Eliza effect is the tendency of people to read more depth into a simple computer program than it really has, if the computer program has some superficial features that invite you to view it as a person. People leapt from "Eliza can do some small grammatical transformations" to "Eliza can think" (or possibly "I enjoy talking to Eliza, even about real things," which is slightly different). People may have been more confused when the Eliza effect was first documented, but people are not necessarily deceived now. Sufficiently tech-savvy people understand what they are doing: they are deliberately "reading" this depth via suspension of disbelief, and playing this imagination game is an important part of playing the game.

Mood aggregates and the camera distance

Maybe this is obvious, but it makes sense to aggregate mood if and only if the camera is fairly far away. In The Sims and Rimworld, the camera is far away, and moodlets are aggregated to form a sim or pawn's overall mood, while in Cultist Simulator, The Sense of Connectedness, and The Quiet Sleep, moodlets or transient influences do not aggregate. If there's a missing resource or obstacle preventing you from doing something, that resource or obstacle is what is depicted, it does not act indirectly through a mood thermometer. (This is a very crude insight, compare it to the sophisticated camera-work described in Itay Keren's talk "Scroll Back: The Theory and Practice of Cameras in Side-Scrollers".)

This might also be a mundane case of "art depicts life". When people direct their attention inward to their inner experience, their overall sense of their current mood fades, or they can dissect their overall mood into more particular phenomena, which are often less unpleasant.

In conclusion

This blog post compared and contrasted 5 games (The Sims, Rimworld, Cultist Simulator, Michael Brough's A Sense of Connectedness and Nikhil Murthy's The Quiet Sleep) depictions of interiority with a framework of 5 different aspects taken from the genre-establishing The Sims (Needs, Relationships, Skills, Job, Moodlets).