Pragmatic ontologies are log-splitters

I want to talk about meditation, introspection, visualization, and using names and symbols as mental tools but I feel like I have to start with a digression about existence because I am worried otherwise I will sound like I endorse woo-woo. This post is essentially a recap and/or response to David Chapman’s post on Vidyam practice.

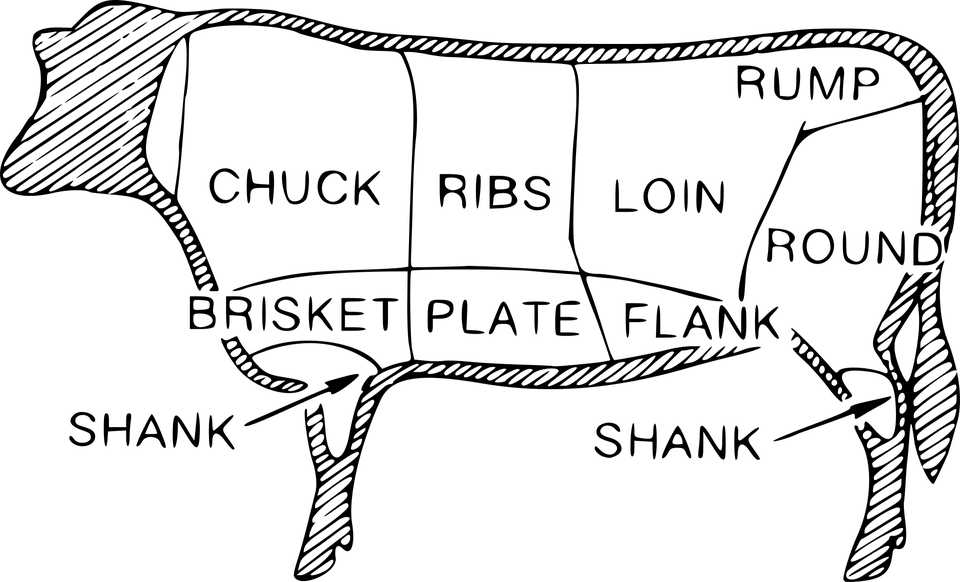

There is an ancient metaphor, from Plato's Phaedrus: A successful theory should carve nature at its joints. To be explicit, a philosopher is like a butcher, and an ontology is like a butcher’s diagram.

A hydraulic log splitter splits a log, which definitely does not have joints. Despite Plato’s recommendations, people do find it helpful, useful, or pragmatic, to apply classifications that do not correspond to “natural joints”, either to reality as a whole, or to parts of reality that they are interested in.

For example, I recently read a book, called “Overcoming Unwanted Intrusive Thoughts”, which divided the reader’s mind into three parts. “Worried Voice”, which responds to thoughts spontaneously and fearfully, “False Comfort”, which habitually offers strategies intended to assuage Worried Voice’s fears (but which turn out to be counterproductive), and “Wise Mind”, which accepts intrusive thoughts and Worried Voice’s responses as passing thoughts but doesn’t validate Worried Voice’s concerns.

I am not an expert, but I believe the idea of dividing the mind into these three parts isn’t current good cognitive science theory. However, this ontology is not for a research project about where the mind’s joints are. The ontology is used to describe mental operations to the reader. Specifically, the mental operation is that the book recommends stopping listening to, believing, identifying with, or behaving like “False Comfort”, and instead start listening to, believing, identifying with, or behaving like “Wise Mind”.

A lot of software leans on these pragmatic, log-splitter ontologies:

- Consider the way an quadtree data structure divides bodies into clusters in Barnes-Hut simulation. Those “clusters” are purely pragmatic groupings, for the sake of efficiency, with no necessary natural joints.

- Another example is Random Forests for machine learning: their splits are made randomly, and yet in ensemble with other random trees, the whole forest can give useful, valuable answers.

- The first step of learning object orientation is usually learning the butcher’s way of OO. Almost immediately subsequently, you have to unlearn the butcher’s way of OO, and learn instead the log-splitter’s way of OO.

There are three practices that I think of as related:

- This “Wise Mind” idea from “Overcoming Unwanted Intrusive Thoughts”, where the authors recommend thinking of your internal self-talk as if it came from these three characters, and identifying with one of them.

- Ignatian meditation, where Jesuits recommend visualizing biblical scenes and identifying with someone in the scene,

- Yidam practice, where Buddhists recommend visualizing a Yidam, an enlightened being, often a deity, and identifying with them.

In all three of these these practices, the historical reality of the character (Wise Mind, Jesus, or Yeshé Tsogyal) being visualized is irrelevant to the pragmatic purpose of the practice.

To be very explicit, a Jesuit might recommend these spiritual exercises to some parishioner, hoping that via these exercises they become more compassionate. That’s what I mean by the pragmatic purpose of the practice.